Charlie Kirk and the Cult of Celebrity Faith

On Politics, Religion, and the Temptation of False Unity

How much do we compromise when we work alongside political movements that are driven, at least in part by other religions, especially when those movements are co-opted for purposes different from our own?

I’ve helped run state political party campaigns and so been involved in this arena myself. And I can say this: I have no problem working alongside non-Christians or people of other faiths when the goal is just. But this is never simple terrain to walk. It requires an iron resolve to never compromise on matters of doctrine and to refuse to promote spiritual falsehoods for the sake of political gain. Often that means saying no! Alliances with those who are not driven by Christ tend to be temporary, and perhaps that’s exactly how it should be. We must hold such ties loosely.

The first thing we need to shake ourselves awake to is this: religion and politics are not separate realms. The so-called “separation of church and state” is one of the greatest cultural myths of the modern age. Wherever there is politics, there is religion, and wherever there is religion, there is politics. The ruling class understands this far better than most Christians. They know the power religion wields, and they are not neutral. In fact, they are often deeply religious themselves, if not in form, then in function and they have no qualms about co-opting religion for worldly ends.

This is especially true when it comes to Catholicism. Rome’s conception of “Church” has always married comfortably with statism. Unlike evangelical Protestantism, which understands the Kingdom of God as something fundamentally separate from the empires of this world, Catholicism has long seen no problem entwining spiritual and temporal power. Church and state strengthen each other in that arrangement, both benefit from suppressing Protestant influence.

This is why Rome’s ecumenical movement is so insidious. On the surface, it looks like unity around Jesus. But the “Jesus” at the centre of this unity is often stripped of his doctrinal substance: a convenient, softened figure designed to lure people in. It’s not unlike the tactics of a cult: find common ground, downplay the differences, and only later reveal what you really believe. By then, the convert has been captured either by a political machine or a religious order, and increasingly the two are one and the same.

This brings me to the current controversy around Charlie Kirk. I don’t claim to have all the answers, and I won’t speculate on every detail. But I do know this: his story does not smell organic. The idea that an 18-year-old built a hundred-million-dollar political machine from scratch is as believable as Mark Zuckerberg building Facebook alone in a dorm room. These narratives are convenient myths, useful to a political establishment for manufacturing legitimacy, but myths nonetheless.

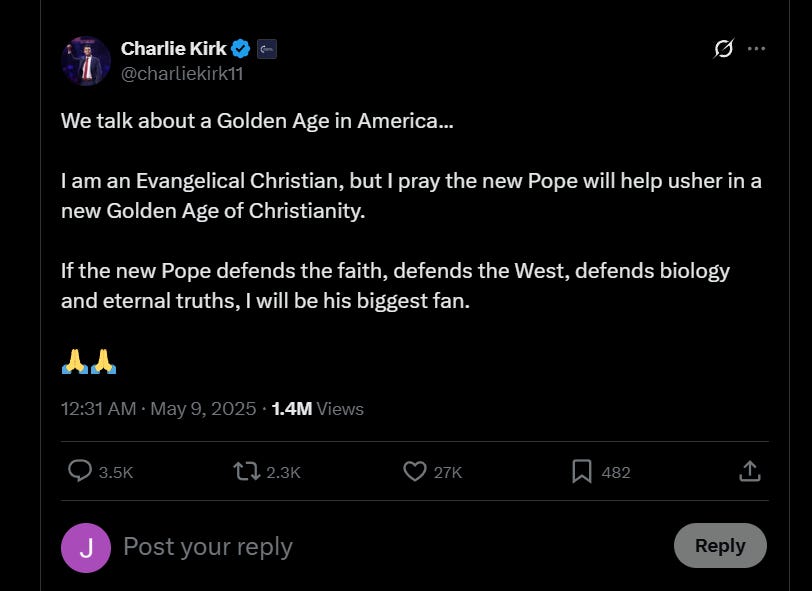

Serious money and powerful interests opened the doors for Kirk, and they did so for a reason. His visible alignment with Catholic figures in media is not accidental. His gradual slide into ecumenical rhetoric is not accidental. It looks very much like part of a broader plan: to capture disillusioned evangelicals and steer them toward a politicised, Catholicised faith movement. And Kirk isn’t alone. Candace Owens’ public conversion, Russell Brand’s newfound spiritualism, Tucker Carlson’s traditionalist leanings, the social media rhetoric from The Daily Wire: all are part of the same narrative. We’re being conditioned to think that spiritual “maturity” means leaving behind the simplicity of the gospel for Rome’s “deep tradition” and even labouring, as Charlie Kirk has hinted, to build a new “golden age” of Christendom under the pope’s shadow and its political reflection in the MAGA movement:

If this is the “revival,” born of Charlie Kirk and those like him then we need to call it what it truly is: a subversion. Yes, God can use anything to bring individuals to faith. But that does not make those movements righteous, nor does it make them our mandate. And when this subversion is dressed up as the next “phase” of Christianity in America, a so-called golden age to be ushered in through papal authority and political power, then we must be even more discerning. Such a vision is not the Kingdom of God breaking into the world, but a man-made empire masquerading as one.

The Real Question Isn’t About Kirk

At a recent dinner I attended, it was asked what we all thought of Charlie Kirk. The consensus was that he was a terrible man, though even his critics admitted he didn’t deserve to die. My answer is this: it’s not really about Kirk. Whether the media paints him as a saint or a devil, both portraits are distortions. Defending him or condemning him achieves little for the gospel in a world where peoples opinions are driven by the social media machine.

The more fruitful conversation is not about Kirk at all, it’s about Jesus and the Bible. People are reacting to this story from deeply entrenched political positions: left versus right, progressive versus conservative. But none of that, in itself, serves Christ. Our mission is not to build idols or martyrs out of flawed men, but to point people back to the Bible’s message.

And here lies a deeper danger: the left–right paradigm is often a tool of divide and conquer, keeping people so fixated on fighting one another that we miss the larger picture. The chaos generated by endless cultural wars is easily co-opted by powerful interests to usher in a “new order”, one that may wear a moral or even religious veneer, but which is neither biblical nor ultimately in our interest. This doesn’t mean we should withdraw from political life or refuse to work within that spectrum, but it means we must engage with discernment, aware that our allegiance is not to a side of politics but to a King and a Kingdom that transcends them both.

Shepherd the Flock: Don’t Chase the Crowd!

There’s another danger lurking here too, one we must name. For centuries, all manner of heresy and corruption in the Church has been justified in the name of evangelism. “If it brings people in, it must be good!” But evangelism is not our highest calling: shepherding the flock is. And if we shepherded better, Christians would not be so easily dazzled by celebrity converts and political movements.

And yet, in our current cultural climate, it is understandable why many Christians grow weary of this posture. We are bombarded with narratives that portray marginalisation as weakness, irrelevance, or failure. For generations, the Church in the West, at least on the surface, has enjoyed cultural respectability and social influence and now, stripped of that privilege, many long to “take back ground” or “reclaim the culture.” The desire is not inherently wrong, but it becomes dangerous when it tempts us to trade faithfulness for influence, or to embrace worldly power as the solution to spiritual decay. The reality is that God has never needed cultural dominance to accomplish His purposes. Quite the opposite: history shows that the gospel’s light often shines brightest in the darkest times, when His people are despised, mocked, and yet unyielding in their allegiance to Him.

If we could embrace that reality, perhaps we would be less tempted by the false promises of cultural influence and more content to preach the unvarnished gospel even when it costs us worldly power.

In the end, the question is not whether we can work with others in the political sphere. We can and should. But we must do so with eyes wide open and our doctrine held in a closed fist. Our loyalty is to Christ and His Kingdom, not to movements, personalities, or those who would twist the gospel into a tool for power.

And above all, we must beware the creeping danger of religious syncretism the subtle blending of truth with error which has always been the enemy’s most effective weapon. The greatest threat is not the loud, obvious opposition of the world, but the soft and smiling invitation to “unity” that demands we set aside essential truths to join hands in false fellowship.

It is so refreshing to read your article. Thank you. Just how we see it.